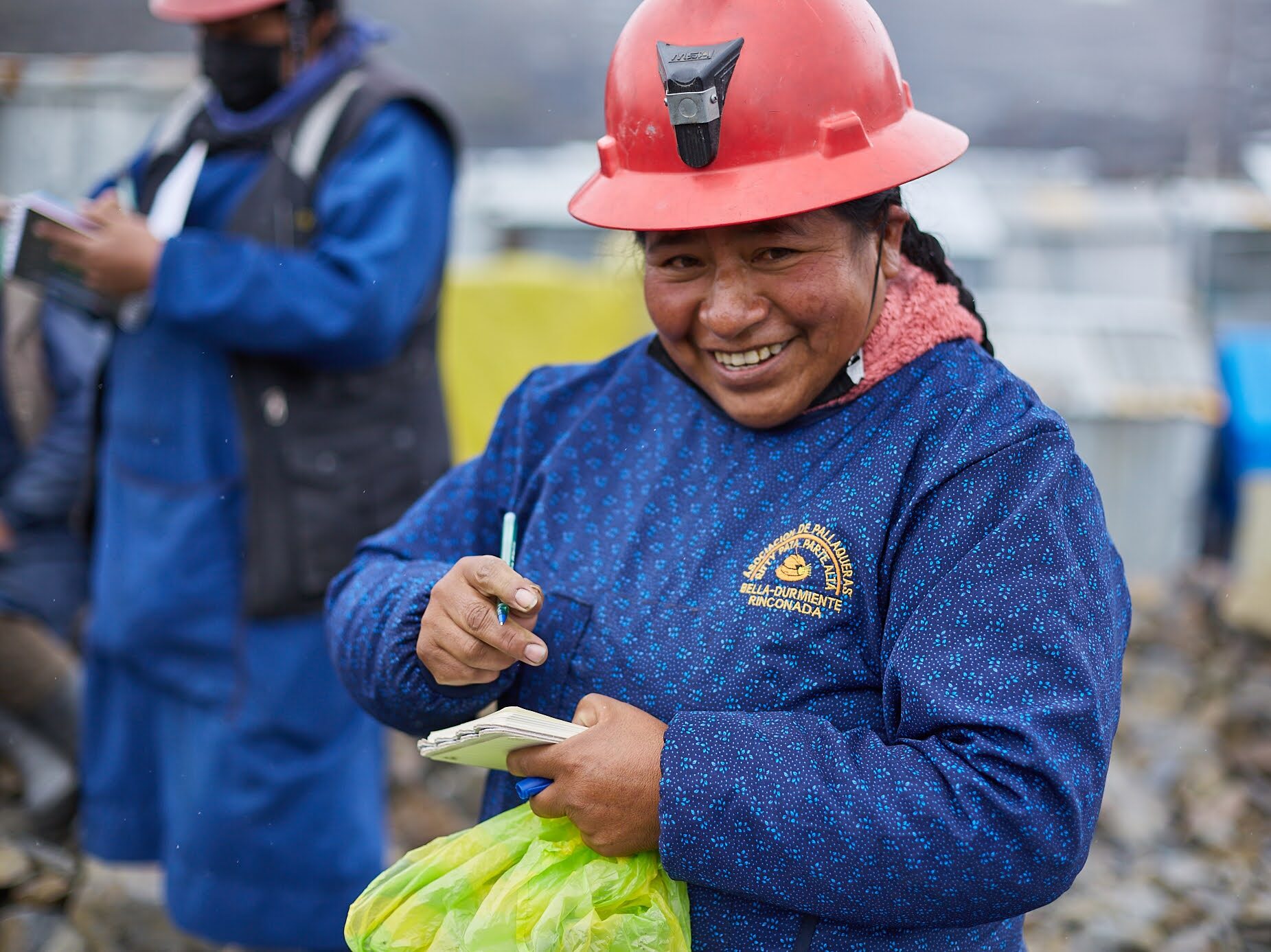

Julia is the president and a founding member of her association, Base La Rinconada, in Puno, Peru. She is also the vice president and one of eight founding members of the first all-women national mining association in Peru, called the National Network of Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (ASM). She’s been her district’s mayor as well. She’s clearly a leader, a politician and an activist, but she claims that she’s still, above all, a miner. She finds motivation in returning home to her daughter and two grandchildren. “I must find a way to divide my time between my organization, my family and, of course, myself.”

What is pallaqueo?

Every morning, Julia wakes up and goes to the mountains to perform pallaqueo. The activity consists of manually selecting ore in the slopes once it has been discarded by their male counterparts who, unlike her, are allowed to work inside the mine shafts.

Julia and her peers have been struggling for years to become formal. Pallaqueo is not recognized in Peruvian regulation, even though it is an ancestral way of mining. This means they will never be part of the formal economy, no matter what good practices they adopt.

Due to this situation, no legal buyer will do business with them. Almost 70 percent of pallaqueras earn less than the Peruvian minimum wage.

There’s not a single legal buyer here, only the black market. But with that money I can buy my groceries and invest in some mining tools.

In 2018, Punean pallaqueras took a step towards formalization, but it wasn’t enough.

In July 2018, the Ministry of Mines and Energy made a statement declaring that several traditional artisanal and small-scale mining practices could engage in legal trading transactions with processors and gold traders. Among these traditional practices pallaqueo was included. But it was only for the Puno region, as a pilot. If everything went well, then the government would declare it nationwide, but this didn’t happen. Julia and her peers can now technically perform trading transactions legally, but they have no trading mechanisms that support them. For example, they still don’t know if they can use a commercial invoice. So, women from Puno are still “one step ahead” of other women miners in Peru, but it hasn’t been enough to find legal buyers.

Nevertheless, Julia hasn’t lost hope, quite the contrary. To achieve her goals, she’s been organizing with other women miners, not only in Puno, but nationwide.

Strong women create strong bonds

Julia believes that the women in her association are strong and wrongly underestimated. In 2013, Base La Rinconada was founded with the aim of finding organizations that could deliver training and guidance so they could defend their rights.

Most of the women in my association are single mothers: abandoned or widows. And everyone tries to diminish them because of that in every aspect of their lives.

In March 2022, in representation of her association, Julia and 22 other women miners from around Peru created the National Network of Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining, with support from the RECLAIM Sustainability! Programme. On the network’s agenda are demands referring to gender inclusive policies, such as the inclusion of pallaqueo as a formal mining activity.

Julia is optimistic about the network’s potential to raise the voice of women working in artisanal and small-scale mining. “We’re going to be able to reach out as one voice. We’ll get to know our rights, our rights to be acknowledged as women miners [by the Ministry of Mines and Energy] but also our rights as women. We must reach out to the Ministry of Women”, she explained.

Julia and Solidaridad

Last year, within the RECLAIM Sustainability! Programme, funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Solidaridad approached women miners based in different regions across Peru to learn about their working and living conditions. There were two meetings in Puno and Julia participated in both of them, as her association’s representative. In these regional workshops, women began to organize with the purpose of creating a national network, with some support from Solidaridad.

With our RECLAIM Sustainability! Programme Solidaridad and partners strive to foster genuine and inclusive sustainability in global value chains, where the voices of farmers, miners, workers and citizens are well represented in decision making, and civil society is strengthened. Gender and social inclusion are an integral part of our programming and envisioned impact.

In November 2021, Julia traveled to Lima, Peru’s capital, to attend a workshop for setting the network’s organizational values and developing soft skills. In March 2022, she returned to Lima to celebrate the National Network of Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining’s legal constitution.

“These workshops have been very useful. They improve our social skills, since we do a lot of things as a team”, Julia says.

Julia is also enthusiastic about how useful the self-esteem exercises in the workshops are.

We need those self-esteem reinforcements. My peers can be very submissive with their husbands, so, after the workshops, I return to my association and share all that I’ve learnt.

In households where gender violence is common, male partners expect women to stay at home and do all the housework. In Rinconada it’s worse, because both partners work outside of the house, and still, women take care of household chores and look after the children, all while suffering domestic violence”, she explains. The network will help Julia and her peers to amplify their voices, but first they must face the challenge of believing in their own strength.

The National Network of Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining is now Solidaridad’s strategic partner. Together we work to raise awareness of the issues that women working in artisanal and small-scale mining face. We aim to create and strengthen the ways in which women can take action together, to help gain representation in the artisanal and small-scale mining sector. This will allow them to effectively participate in public and private dialogues to improve their labor conditions and overall livelihoods.

Challenges and dreams

Even with all her duties, Julia still set herself a new goal for the year. She wants to build her own house with her own resources in her homeland. And she wants to spend quality time with her family there.

Julia takes great pride in her accomplishments, but she explains that the most valuable achievements for her are family-oriented. “I’m proud of everything I’ve accomplished, but there are two things I’m most proud of. First, that my daughter has her own family; a good husband and two children. I’ve even thought that if I wasn’t a miner, I’d be trading ceramics, since my son-in-law is a talented artisan. And secondly, and much more personal, was meeting my mother. I met her when I was 29-years old”.

So far, nearly 450 women miners are affiliated with the National Network of Women in Artisanal and Small-Scale mining. There are more representatives like Julia who are deeply interested in making their communities and country a better place for women miners.