Local knowledge systems, social structures, and preferred communication channels are all critical to effective data collection. For example, in some communities, the data collection may require the involvement of traditional leaders or community meetings to discuss the data and its implications. This means that collection processes should be participatory and inclusive.

Small-scale farmers in Africa are an integral part of the global food supply chain. Yet they face myriad challenges, including poor infrastructure, low literacy and digital literacy levels, and additional vulnerabilities brought on by climate change. These challenges complicate farmers’ access to information and resources that could improve their productivity and help them adapt to changing conditions.

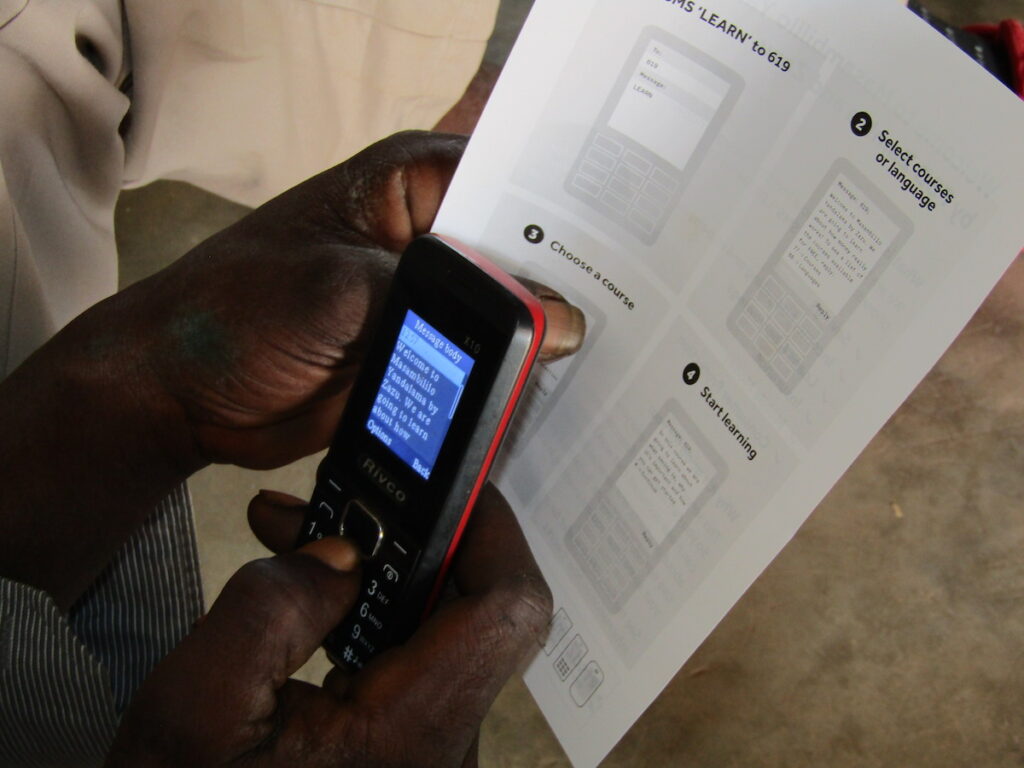

In recent years, technology has been promoted as a solution to these challenges, however, low smartphone penetration rates in Africa, coupled with the low literacy levels, make it difficult for small-scale farmers to benefit.

A farmer-led approach to data collection

Data collection can be improved using a lead farmer model that involves training a small group of farmers in a community to use digital tools and collect data. These farmers can then share knowledge with others and act as digital secretaries for their community. Although the initial data collected may be of low quality as lead farmers learn, it will improve quickly over time as farmers become more proficient with digital tools and data collection techniques.

The low literacy and digital literacy levels in Africa mean that traditional methods of communication, such as oral communication and demonstration, are more effective than written communication. The lead farmer model leverages these traditional methods of communication and makes use of existing social systems, making it easier to disseminate information and knowledge in the community.

African cultures are communal by nature, empowering one person has a spill-over effect, sharing is innate. This makes the lead farmer model cost-effective and scalable.

Candice Kroutz-Kabongo, team lead: digital innovation at solidaridad

African cultures are communal by nature, empowering one person has a spill-over effect, sharing is innate. This makes the lead farmer model cost-effective and scalable. By focusing training efforts on smaller groups, outputs can be monitored more closely and challenges identified sooner. Though training lead farmers takes time and resources, they can become valuable assets for their community. Moreover, the lead farmer model is a long-term, sustainable investment.

Potential impacts of locally-led, culturally-relevant data collection

The potential of this data is significant. By collecting data on weather patterns, soil moisture levels, and other environmental factors, farmers can adapt to changing conditions and mitigate the effects of climate change. It can enable the provision of site-specific advisory services to farmers, which can help them optimize their yields, crop selection and planting dates.

Additionally, the data can be used to link farmers to new markets and increase their bargaining power. This not only benefits the farmers, but strengthens the entire value chain.

Connecting service providers to small-scale farmers can be facilitated by the lead farmer. Once the data is collected and analyzed, service providers such as agricultural input suppliers, financial institutions, and insurance companies can use the information to design and offer more targeted and relevant products and services to farmers. By doing so, service providers increase their reach and impact on small-scale farmers, thereby improving their own profitability while contributing to the productivity and resilience of the farmer.

The lead farmer model can be particularly empowering for women in African small scale farming communities. Women farmers often face more challenges than their male counterparts. These include limited access to land, credit, and education.

The lead farmer model provides an approach that is both sustainable and culturally sensitive. Ultimately, the collection of data from small scale farmers in Africa using the lead farmer model should prioritize relevance and usefulness to the farmers themselves. While scientific rigor is important, it should not come at the expense of practicality and local context.

The model can provide a platform for women to network and share knowledge with other female farmers in their communities. By involving women lead farmers in data collection, and information dissemination, the model can help break down gender barriers and improve female participation. Women can increase their collective bargaining power and advocate for their needs and interests in the agricultural sector.