“A rush against the structures of injustice will not bring us anything positive. We have no choice but to opt for ‘the long march through the institutions.”

Frans van der Hoff

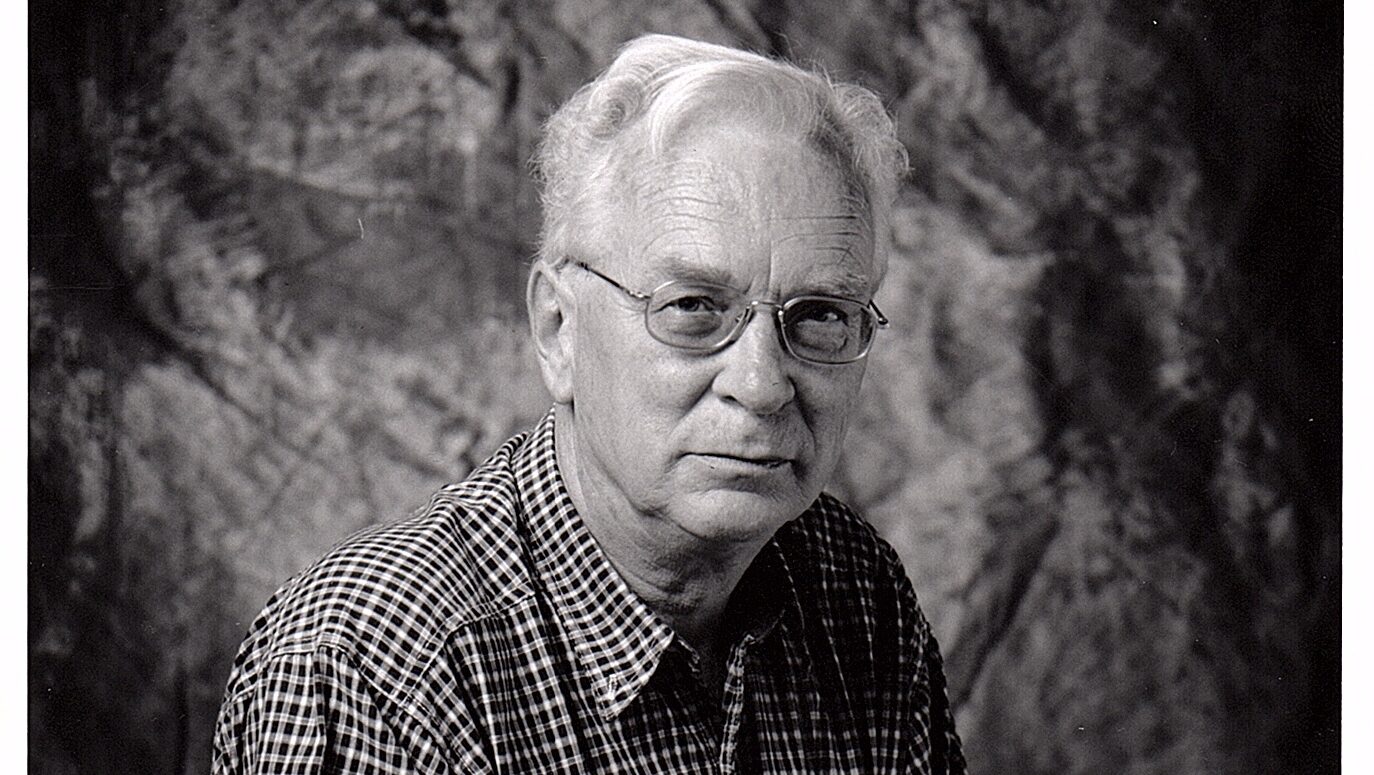

Frans was born in 1939 in the small village of De Rips in North Brabant [Netherlands]. He was the sixth among sixteen children from two marriages. Frans grew up in a Catholic family where the seminary or a monastery were the only options for further education if you came from a poor background. Monastic life was disciplined and strict. But Frans and a group of other novices broke all the rules, and the Beatles were sung instead of the psalms.

These were turbulent years. The Second Vatican Council opened the doors of the church to the world. Frans was eager to learn and already an activist at heart. He came into contact with the theories of Marx and became active in the Third World movement, a Dutch solidarity movement. He studied with the Belgian theologian, Edward Schillebeeckx, and economist Jan Tinbergen. Frans was ordained as a priest in 1968. An ordination that was all about the consistent choice for the poor, knowing that this choice could lead to all kinds of forms of repression.

After a period of working in a shelter for drug addicts in Ottawa, Canada, he moved to politically turbulent Chile. After the situation there became too dangerous for him, he continued his work in Mexico where the progressive bishop of Tehuantepec offered him a home base. There he found the workplace of his life.

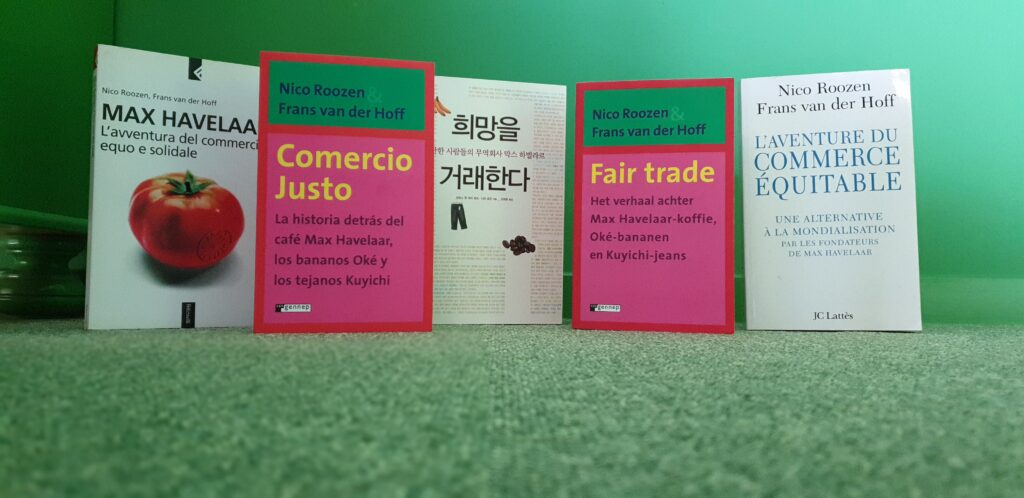

Van der Hoff and Roozen wrote a book together on the foundation of the fair trade movement, which was published in five different languages.

The problems of indigenous communities fascinated him; disadvantage and inequality rooted in identity frustrated him. He saw the incipient organizing of coffee farmers into the UCIRI cooperative as a feasible mobilization of social and economic forces that could not be smothered with violence. And the ordinary farmer’s life, which he knew from home in the Netherlands, attracted him. This became his path in life. A path that united his political and religious beliefs.

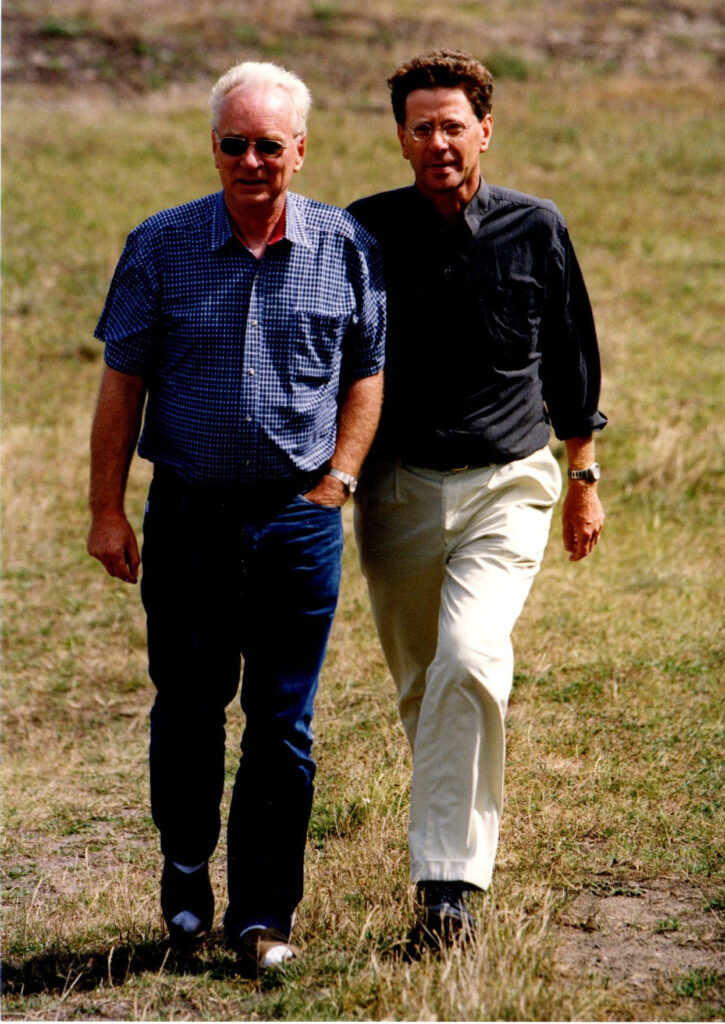

In 1985, Frans met Nico Roozen of Solidaridad in Utrecht, the Netherlands, where they discussed how they could dramatically increase the market share of sustainable coffee by organizing the availability in supermarkets. They agreed that UCIRI would build a broad network of coffee farmer cooperatives in Latin America to meet the future demand for sustainably certified coffee.

Solidaridad would organize the further expansion of cooperatives and associations in Africa and Asia, and develop a quality mark that could facilitate market introduction in Europe, starting in the Netherlands. Their joint agenda transcended traditional aid relationships to mix social and economic justice.

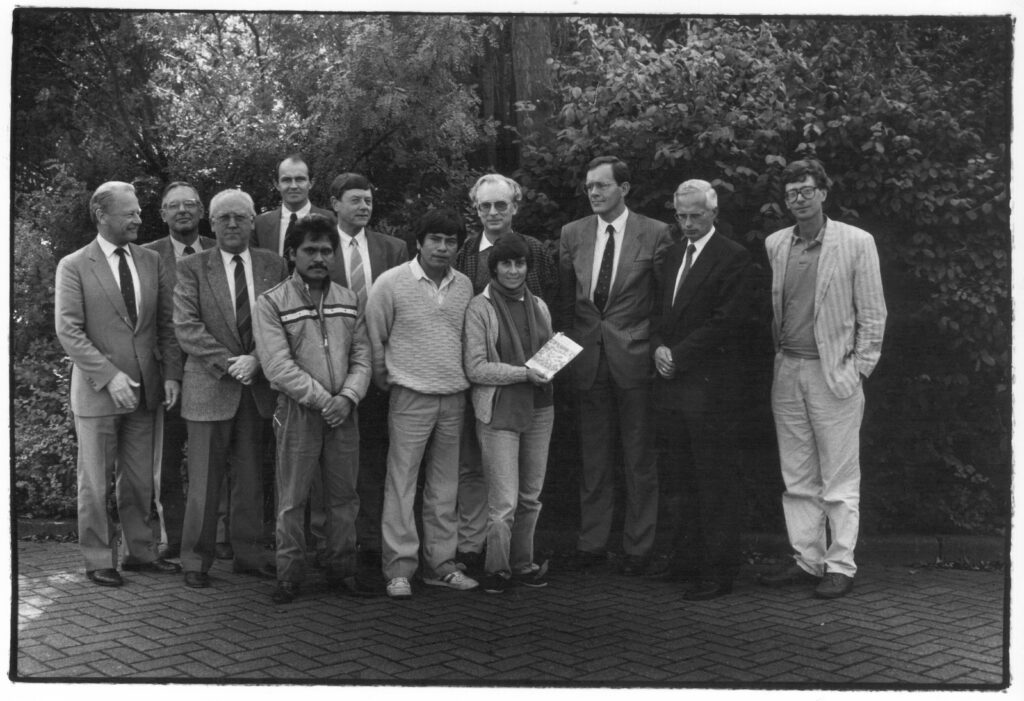

It would take three years before the Max Havelaar certification would make its debut in the Netherlands, and the long road to European expansion began. To accelerate the momentum, a large UCIRI delegation came to the Netherlands to promote the plans and consult with Dutch coffee roasters and supermarkets. Resistance among the major roasters, led by Douwe Egberts (now: JDE Peet’s), was severe and these companies worked to prevent the introduction of the certification. This resistance only validated the strength of the fair traders’ approach and made Roozen and van der Hoff even more insistent.

A little more hope for a few more people

Frans van der hoff

Thanks to the tenacity of Frans, Nico and the farmers of UCIRI, Fair Trade labels have become an indispensable part of markets around the world, building solidarity between small-scale farmers and consumers.

Despite this significant contribution to social change, Frans was modest and never prided himself on his achievements. He preferred to talk about his shortcomings and said he only achieved a little more hope for a few more people.

Frans died in the farming community that he loved. Their strong connection between him and the community was mutual and he will be dearly missed.

Read Nico’s full article (in Dutch) here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/francisco-petrus-van-der-hoff-boersma-1939-2024-nico-roozen-msv4e or in Spanish here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/francisco-petrus-van-der-hoff-boersma-1939-2024-nico-roozen-tegce/