Sinforosa, better known as Sinfo, is the oldest of nine siblings and a native of Porco, a municipality in Potosí, Bolivia. When her father fell ill with a lung disease called silicosis, he wrote to the Encarnación Mining Cooperative and requested for Sinforosa to replace him as a member of the mining organization. “My dad inspired me as a leader to be brave. My dad never differentiated gender roles,” Sinforosa says nostalgically. “But in the beginning, it was very difficult to take part in the Cooperative. Leaders showed a ‘macho’ behaviour and used to kick out the widows of those miners who had died in accidents or from illnesses from the cooperative. When my father passed away, they could have kicked us out too, but thanks to the fact that he left a letter behind, I was able to participate and enter the mine.”

My dad inspired me as a leader to be brave. My dad never differentiated gender roles.

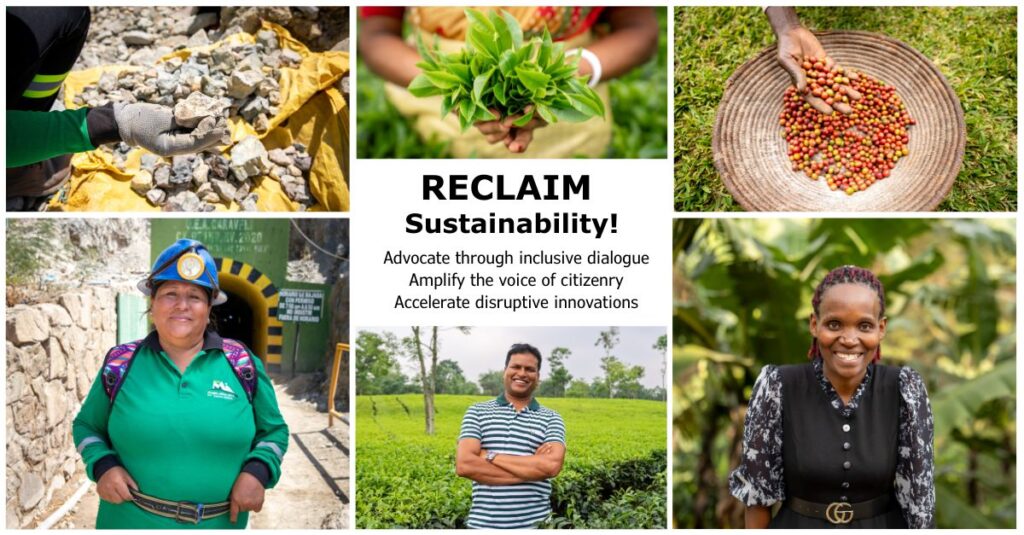

Sinforosa rodriguez, miner

Overcoming barriers

There are different barriers for women to participate in the exploitation of the largest mineral reserves: from the preconception that women are not physically fit for mining to the superstition that letting women inside the mine brings bad luck. The Encarnación mine was no exception to this rule, but Sinforosa paved the way for other women relying on her father’s support and her own determination. She started in the cooperative as a cashier, where she demonstrated her skills and responsibility, and from there she rose to become interim president of the cooperative.

Getting the opportunity to join the cooperative was just the first step. Sinfo had to build many of the necessary skills for her role. “I couldn’t express myself, I couldn’t,” says Sinfo. “At the meetings of the Federation of Cooperatives I was afraid to face the other cooperatives. I didn’t have that capacity to express myself.” Realizing her limitations were shared with other women companions, Sinfo went to La Paz and sought support. Through the Unitas organization, she got in touch with the National Network of Women and Mining of Bolivia.

In the Network she met other Bolivian mining women with different occupations, but similar challenges. “When I entered the Network I found an opportunity to make my colleagues known. We started working on our self-esteem and talking about bravery. We started organizing ourselves within the Network. There were housewives, gold producers from cooperatives, palliris and barranquilleras.” That’s when Sinforosa met for the first time the “barranquilleras”, women gold panners. “They, like me, were too afraid to express themselves,” she remembers.

Sinforosa joined two of the strategies Solidaridad was executing with the Network. One was strengthening the organizations and their members to lead and carry out political influence work effectively. The other was to reactivate the National Network of Women and Mining as a meeting space and platform for women collective action. The capacity-building work was accomplished through workshops and training lessons and then put into practice by preparing policy recommendations and attending internal and external dialogue events. As a result, 80 percent of the women participating stated they had strengthened their capacity to propose policies, and 60 percent that they had improved their abilities to speak in public and express their ideas. In addition, 60 percent of the women reported having improved their knowledge of occupational health and safety, and of the situation of women in gold mining.

At the organisational level, the Network submitted a political agenda for women miners, based on the inputs of more than 120 women miners who attended workshops and meetings organized by Solidaridad and Cumbre del Sajama. The proposal holds recommendations on health, education, gender violence, environmental care, and to conduct a census, which earned the attention of the Mining and Metallurgy Ministry (MMMS), laying the groundwork for the elaboration of public policies.

“I am what I am, a leader, because of my fellow members (at the National Network of Women and Mining). They recognize me as does the State. Now, when I go to meetings, I introduce myself as part of the Network. I was introduced to Law number 348, and was taught that I should not let anyone humiliate me. I began to tell my president, enough! you are not going to order me around.

Sinforosa rodriguez, miner

Law number 348 aims to establish comprehensive mechanisms, measures and policies for the prevention, care, protection and reparation of women in situations of violence

Sinforosa went from not being able to express herself to providing statements for a national newspaper about the situation of women miners during the Covid-19 pandemic. “I am what I am, a leader, because of my fellow members (at the National Network of Women and Mining). Now, when I go to meetings, I introduce myself as part of the Network”. She knows her rights and has concrete proposals: “I was taught that I shouldn’t let anyone humiliate me. I began to tell my president, enough! you are not going to order me around”. This path has led her to take on a new challenge: bring the voice of women miners to the Bolivian Legislative Assembly. Women like Sinforosa have not just challenged the myth that women cannot enter the mine. Now they are going to show that they can also get into the National Congress.