Current emission trends are sobering, and in sharp contrast with the objectives set out in the SDGs and Paris Agreement. The INDCs submitted by countries so far would, if fully implemented, result in more than 3 degrees of warming by 2030. This level of warming is catastrophic for people, the planet, and business. Even if countries raise their ambitions to reduce emissions, the adverse effects of climate change globally will almost certainly worsen in any event, as a result of greenhouse gases that have already been emitted. The prevention of these catastrophic events requires a global shift to clean green economies, whereby businesses and countries can drastically reduce their emissions to reach zero around 2050.

Confronting complexity

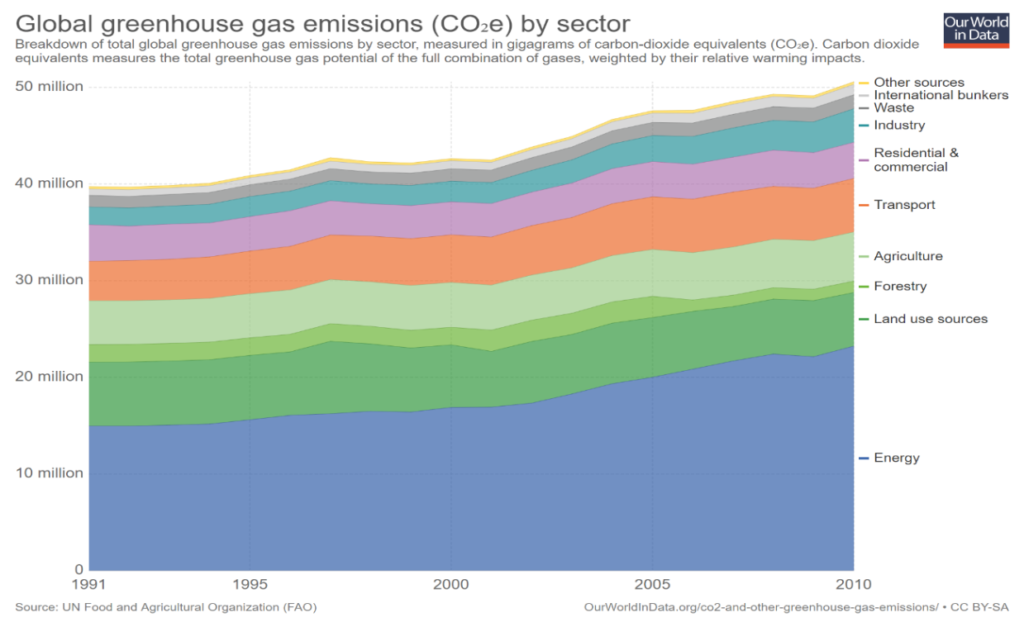

After energy production, the agriculture, land use, and forestry sectors combined have the highest rate of CO2 equivalent emissions and together account for about 25 percent of global emissions (IPCC, 2017). Unlike the industry and energy sectors, however, the agricultural sector does not show exponential growth of GHG emissions. Emissions from deforestation (‘land use sources’), responsible for about 12 percent of emissions, were roughly stable between 1991 to 2010. In the same period, global agricultural output increased by more than 50 percent, and output in developing countries doubled (USDA-ERS, 2017), so GHG intensity was reduced significantly.

The green revolution has made it possible to increase agricultural output globally but is heavily dependent on fossil fuels (irrigation, mechanization, synthetic fertilizers, and pesticides). And although emissions per unit product are expected to continue declining, absolute emissions and associated pollution are expected to continue growing. The synthetic inputs themselves (Nitrogen and Phosphorus in fertilizers, biocides) also affect ecosystem health and services, and in some cases the adaptive capacity of ecosystems and communities.

The Covid-19 pandemic is a good example of what happens when an ecosystem’s health is compromised. Zoonotic diseases are on the increase as a result of the expansion of farmland into forests. The Covid-19 pandemic has had devastating socio-economic and environmental impacts on the business of food throughout the value chain. Producers and consumers alike have been affected in a myriad of ways.

Demand growth from agriculture is expected to increase as many sectors transition from fossil to bio-based raw materials. Thus, there is a risk that agricultural sector emissions will increase rather than decrease in the future, which is not in line with the Paris Agreement targets. When assessing the situation from the point of view of greenhouse gas emissions the question is:

How might agriculture, as a sector, sustainably contribute to the reduction of emissions even with the growing demand?

It is precisely here that holistic agroecological approaches can help us to find adaptive solutions to this complex problem.

The politics of global warming and global markets

The governments of the global south are confronted by the need to feed their young and growing populations, modernize economies, and eradicate the pandemics of inequality, poverty, and disease. In the African context, what is required is a dynamic and responsive approach to support African countries’ attainment of Africa’s Agenda 2063 aspirations, relevant Sustainable Development Goals and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Paris Agreement targets; delivering impactful interventions and recovery from the pandemic whilst transforming and catalyzing Africa’s sustainable development towards a low-carbon developmental trajectory by 2030.

Policy Advocacy

“Jai Jawaan Jai Kisaan (Hail the Soldier, Hail the Farmer)” is a chant that we have heard on international media networks in the last few months as Indian farmers protest the introduction of new agricultural policy measures by the government. One of the lessons from the Indian case is that there is still a need for governments in the global south to blunt the effects of economic cycles by providing cushions from climate hazards (droughts, cyclones, and monsoons) that disproportionately affect farmers. It is in this context that farmers are being asked to adopt regenerative/climate-smart practices (assuming that they are not already doing this) with the promise of increased productivity over time, and more importantly, ecosystem protection and mitigation of climate change (which is the higher aspiration).

Policy advocacy is thus an essential service that organizations such as Solidaridad (supporting farmers) must deliver, to help farmers to adapt to a rapidly changing climate. Policy instruments that subsidize the adoption of regenerative practices are essential to incentivizing behavior change. However, these policies need to be farmer-centric and promote fair value distribution across commodity value chains.

Gender and economics

Precious Greehy and Mandla Nkomo reflect on the history and future of women’s economic participation in Southern Africa, and Solidaridad’s efforts to level the playing field.

Carbon Markets, a neo-liberal experiment

In “No Regrets: Why Carbon Sequestration is Agriculture’s Biggest Job” a webinar series presented by Heifer international, the deliberation focuses on some adaptive questions such as: who benefits from carbon markets? How do we solve for inclusion, and unlock value for farmers? Is this yet another neo-liberal experiment that will eventually be appropriated by big business? The hope is that when the Covid-19 pandemic ends, we can build back better by building economies and markets based on diversity, inclusion, and the recognition that women do the lion’s share of the work and get the least rewards for it.

Adaptation and Mitigation

In his new book, ‘How to avoid a climate disaster,’ Bill Gates proposes that carbon trading and policy advocacy are our biggest levers to reversing climate change. Convincing governments across the world to act decisively to reduce GHG emissions, responsible sustainable consumption by citizens, and a fair carbon market is the work that we all have to do.

A strategic lens

Under Solidaridad’s new 5-year (2021-2025) strategy Reclaim Sustainability one of the primary goals is to reduce the environmental and climate footprint of food systems where we work while strengthening its resilience in the face of climate change and other global pressures. Hence, we have developed a comprehensive food systems approach to address food challenges, taking into account all the people and activities that play a part in growing, transporting, supplying, and eating food. Solidaridad champions holistic management practices in all our programming, as well as the promotion of adaptive and mitigative interventions. Holistic agriculture has emerged as a common-sense response to climate change. Focus on soil health, and management has become mainstream, and with that, space has opened up for a different conversation.