Nothing short of a global transformation of the food system will be needed […]. In short, if we get it right with food, we get it right with everything else.

Johan Rockström, Executive Director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre

Our food system has both social and environmental implications, and its flaws are manifested in hunger and health crises around the globe, with significantly large portions of biodiversity and arable land at risk. Agri-food is the world’s largest economic sector with half of the world’s working population active in agriculture. Globally an estimated 2 billion people work in the food system. In emerging and developing countries an estimated 200 million smallholder farms are connected formally or informally to agricultural food chains. These include both urban and rural growers. In a vicious cycle our food system generates about 35 percent of total global man-made greenhouse gas emissions and with global warming agriculture production is increasingly compromised.

But not only are biodiversity and climate outcomes adverse; the way our food system is currently organized has narrowed down people’s possibility to opt for fresh and healthy food. Staple food has been dominant in our diet, while cheaper, processed food, high in fats, sugar and salt, has become the best available and most promoted food around the globe. The same is true for what we drink, with billions of people having better access to high sugar sodas than clean drinking water. In 79 of out 82 countries studied between 1990 and 2016, sodas appeared to be more affordable than bottled water and have become the preferred drink of billions of people worldwide (Newsweek).

High-value horticultural markets improving livelihoods

The “Smallholder Access to High-Value Horticultural Markets” project helped emerging farmers access high-value markets in South Africa and obtain certification under localg.a.p.

Africa produces enough to feed the rest of the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, the majority of countries are net exporters, but are unable to feed themselves. This is fundamentally unfair and disadvantageous. Africa must improve and expand agricultural production and country governments need to redirect their food focus to feeding the continent first, before then the rest of the world. However, in the current food system Africa fails to provide adequate food availability, food access, food quality, food utilization, and stability for most Africans. Global supply is prioritized over local food supply. Food insecurity and poverty therefore, remain high, and the majority of livelihoods on the continent do not have adequate incomes to maintain households’ resilience and adequate access to affordable and healthy food.

Our food challenges are increasing

In the near future, over 80 percent of the world’s food will be consumed in cities. With 90 percent of the population growth taking place in Africa, fast urbanization will bring a dramatic pressure on arable land and on water, two necessary resources for food production, particularly in Africa. By 2050, the global population would have risen to an estimated 9 billion people and on the African continent the population is expected to double to 2.4 billion. Besides climate, the highlighted food challenges will also grow exponentially, especially in urban centres, because of the increase in food demand in combination with the above mentioned consumer dietary shifts to uniform diets of more processed food products. Together with a lack of purchasing and financial power, innovation capacity and policy influence by vested industry players to maintain status quo, these tendencies seem hard to turn.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown that any shock or disruption deepens social exclusion, food vulnerability (such as inability to access food) and food inequality (such as unaffordability of food), especially in economically-disadvantaged areas of cities where there is relatively poor access to healthy and affordable food.

Food systems in Africa show a very complex nature of informal food systems on the one hand, and industrialised systems on the other. The informal food system, dominated by smallholder farmers, is characterized by deficient production methods and inputs leading to inefficient and inadequate use of resources, low yields, lack of capital and low investment potential, deficient access to markets, low income and lack of motivation for farming. The industrialized food system is characterized by unequal power relations, and unequal benefits and value distribution within supply chains, unsustainable high input farming practices, and emphasis on highly processed, cheap and unhealthy food products for the many, as opposed to a healthier and more diverse, but relatively expensive food offer (fresh and nutrient-rich) for the few.

Many research outcomes have shed light on the overall impact of these industrialized food systems on nutritional food security and public health, but also on animal welfare, social justice, climate justice, environmental justice and food sovereignty. The need to transform them by authentic solutions has become obvious and urgent. But how do we build food systems that are sustainable, efficient, resilient, integre, equitable, inclusive and diverse, embedded in a culture that promotes health for people and the planet?

What does a nourishing, sustainable, inclusive, healthy, resilient and efficient food system look like for Africa?

It is becoming more and more clear that many of the problems we face are interconnected, and that we therefore need more holistic and interconnected strategies, aiming at changing the food system as a whole. Cities and urban centers could be the key driver for food system change. Particular attention is required to ensure shorter food chains, where local producers are primarily and as directly as possible connected to local food systems. We need healthy food to reach people, support transitions to healthier diets through the promotion of nutritional and healthy consumption and reduce high levels of food waste (primarily at the conventional food systems) production and consumption level, while we ensure sound agricultural practices.

Biodiversity protection

Mandla Nkomo and Lisa Mbwia explore pathways for enhancing farmers’ agency.

However, there are major contradictions around sustainability and fair, resilient food systems. Over the last two decades we have seen an emphasis on sustainability. Global sustainability goals have been set with governments. The private sector became the front runners in adopting and reporting on sustainability standards and civil society and nongovernmental organizations rigorously advocate for sustainable development, that leaves no one behind. But why do we continue to have persistent power imbalances at the production level, within the food supply chain and the concentration of power with few conglomerate food players that maintain the status quo of and make it difficult to achieve systemic change? Why do we have a food system that feeds some better than others? Is how we are defining sustainability maintaining the brokenness of our food system? Why is it that we have sustainability that means one thing for some and something different for others? To find integrity in the food system therefore requires defying the paradox of sustainability. Through finding a common sustainability agenda that drives alternatives to industrial agriculture and food processing and production, and developing holistic integrated policies capable of shifting us toward a more sustainable range of food production, consumption and supply chain options and a healthier, inclusive food system.

In a food systems discussion with WWF South Africa in April 2021, facilitated by Solidaridad, the dire case of South Africa and the current state of climate change impacts on our food system had been highlighted. Concerning facts were raised such as urban sprawling and loss of agricultural land and biodiversity, water scarcity and unjustifiable food waste. These are not only characteristics of South Africa, but the global south. Food system transformation will require working with and integrating context-dependent combinations, linking knowledge and methods from different disciplines. It will require working with all food systems players, from a community of farmers to academics, retailers, food industry players, food designers, NGOs, health advocates, environmentalists, scientists, certifiers, researchers and consumers.

Where to start?

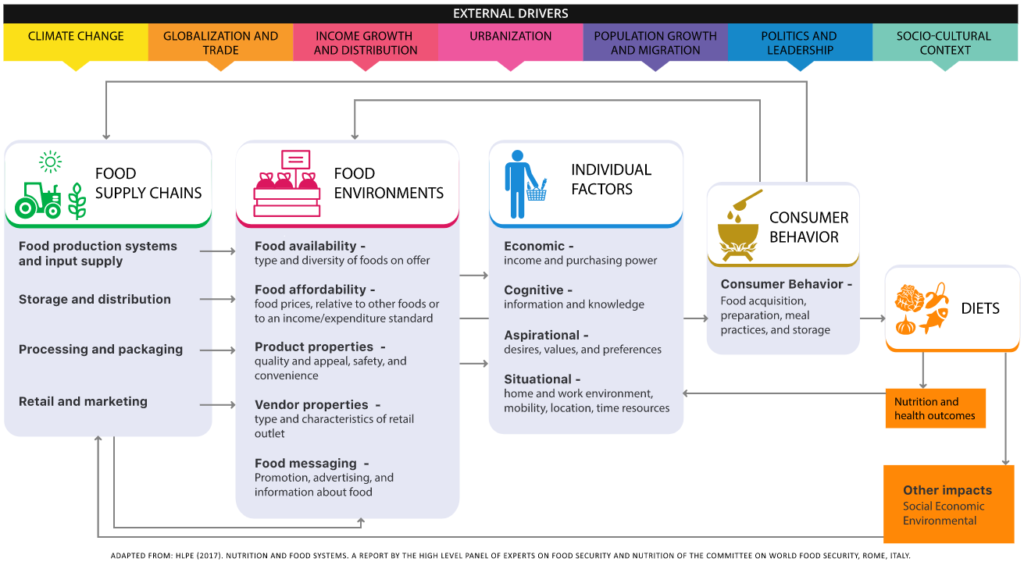

Amidst all the complexity, the main question is: where to start? What is the most powerful approach to get the wheel spinning? The most critical tools for action for positive change are WE, the consumers, making healthier food choices. Any action will have to aim at enabling consumers to actually make these choices. This starts with building sustainable supply chains and optimizing food environments to make them supportive to healthy food choices. In addition to that we will have to work on the individual factors that need to be overcome and enable and support consumers to adopt a food behaviour that is supportive to the change we need and seek.

Based on regionalized interpretations of the EAT planetary health diets, we can influence and support what and how farmers produce food in agro-ecological, biodiverse, regenerative and circular approaches, creating local and international communities of food, together with by the many champions active in all aspects of the food system who want to contribute to real sustainability. Only people can bring about authentic solutions to reshape food systems.

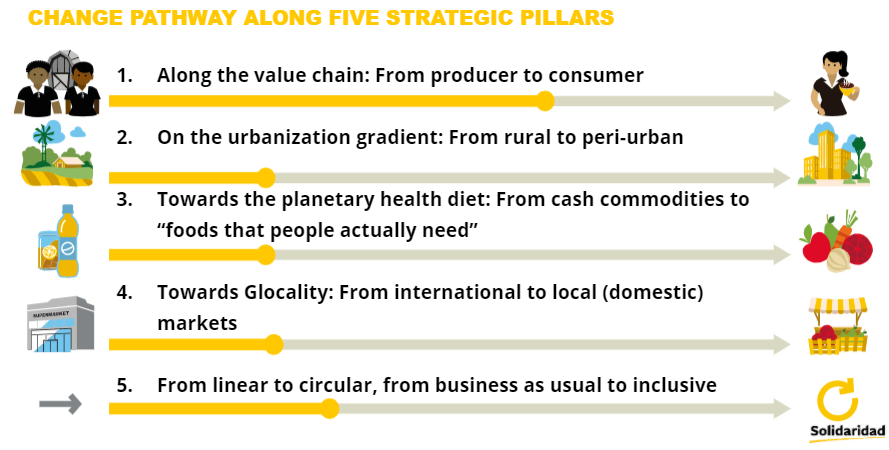

For Solidaridad this means we have to not only work towards improving current on-farm practices in existing commodities in the different regions on the continent, but in parallel contribute to redesigning and innovating the current food system and seek strategies that combine regenerative and rewarding farming practices with interventions aimed at creating local food system connections and even supporting dietary changes. We need to contribute to building food systems that are more balanced in terms of local versus export markets, serving local needs and decreasing dependence of developing countries on unhealthy cheaper food imports while healthy foods are exiting our continent. Food systems that are more diverse and localized, well embedded in local cultures and supportive of more traditional diets. With crop varieties that are more suitable for local production conditions and therefore require less inputs and increase farm resilience in different ways.

Co-creating contours of a new food system in Cape Town

Some people define sustainability in terms of enabling existing operations, growth and development to continue. For others, sustainability is living within the boundaries of what is possible given the finite resources of our planet. Reconciling the two requires transformational leadership.

Colin Coulson-Thomas

Many examples of innovative solutions for different elements and aspects of the food systems already exist, for us to build on and connect and combine into transformative solutions. Next to the efforts that have to be made to transform the formal food system, we need to invest in initiatives that are emerging from the informal food system. With food security increasingly seen as an urban concern, in all the major South Africa cities, urban and peri-urban agriculture has emerged as one strategy for improving access to healthy, affordable food within cities.

We have seen significant increases in home gardeners, community gardeners and gardeners participating in community food security, providing low-income families with food availability, accessibility, nutritional adequacy and cultural acceptability as well as agency within the food system. Urban gardens also increased low-income households’ access to healthy food, allowing (even if in small measures) healthier diets which they could not otherwise afford to purchase. Increasingly gardeners do not think of cultural acceptability strictly in terms of the presence of certain types of cultural crops; they also articulate a broader set of values concerning the environmental and social conditions of food production. Among low income gardeners what we are seeing emerging is a set of food values related to knowledge, control, trust, freshness, environmentally sound production methods and sharing, which they were able to enact through gardening. Taken together, it’s a demonstration of the nutritional contributions that urban gardens make, but it also highlights the importance that low-income gardeners place on having food that aligns with their cultural and ethical values and being able to exercise greater autonomy in making food choices.

One example coming up globally is community-based agriculture, which looks to create direct connections, participation and ownership of consumers in food production. We can learn from solutions in different parts of the world that have proven to be effective and create new and resilient food connections and solutions. Like the Dutch ‘Herenboeren’ or Farming Communities concept which is internationally gaining attention and whose initiators are looking for ways to support the development of this concept of ‘community driven food production’ in other parts of the world as well. And now, mix it together with great local initiatives like ‘Seed to Harvest’ and land reform specialists like Phuhlisani, and the recipe for community based food systems change is boiling.

What lies ahead for Solidaridad?

Seeing anew would take not just crafting new answers to our most intractable problems but finding new questions – new ways of asking. Our vocation must now be to seek out questions and to come to the places where we are “undone”.

Bayo Akomolafe

Resilient food systems need alternative and innovative strategies that take the integral importance of economic, social, ecological, political and cultural factors seriously. Hence setting a resilient and sustainable food system is embedded in three trajectories for Solidaridad:

- The current food system must change by analysing carefully and critically our existing interventions to understand the actual change they bring and to see how we can make them more transformational. Key words are inclusion, new power balances, regenerative, circularity, ‘glocality’, benefit sharing and future proof, as laid down in our new Multi-Annual Strategic Plan, ‘Reclaiming Sustainability’.

- The system we want to transform to, is a food system that supports people’s health and is based on food equity, equality and democracy. And a food system that supports the planet, by restoring the damage done and making it future proof. As Solidaridad we should (co-)create a clear picture of the transformed food system we want to work towards and which we can help achieve, building on past experiences and the expertise built from these.

- Work towards enabling the necessary changes to break the current dominant patterns of the food system we want to transform by supporting the beginnings of alternative food systems and food pathways.

Lessons and insights from our own work and that of others have provided us with an enhanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms and factors that impede systemic change. While we relook at our current interventions and draft the contours of a new food system, we need – in parallel – to act on the necessary changes and build on different types of innovative initiatives that can support and form part of this change, and that contribute to food system transformation by putting in place new, disruptive solutions. In countries and among regions on the continent, in partnership with champions – individuals and movements – of the envisioned new food system, the time to build, reshape and develop transformative solutions to food system change is now.

We need to move towards supporting better nutrition, leverage technologies and find solutions for sustainable, inclusive and just food systems. We must strengthen resilience in the food system in such a way that the economic, social, and environmental foundations to produce sufficient healthy food maintain healthy ecosystems without compromising current and future generations. There is no silver bullet, but through scenarios, we can look at potential pathways and identify the drivers that can create a conducive enabling environment. Solutions must contribute to shifting operational models and underlying rules, incentives and structures, in order to shape food systems that can advance global goals that can be sustained over time. We have to explore how to navigate the future of food, by defining Africa’s food systems, understanding how Covid-19 has shifted or is shifting innovation and nutrition security and identifying what transformative scenarios show signs of becoming the new normal. Hence, consider critically, how we as Solidaridad could navigate the future of food in contributing to defining and redesigning tomorrow’s food systems. We have worked relentlessly in the past decades for more just and equitable supply chains and sectors. Now it is time to build on our lessons learnt, start putting the pieces of the puzzle together and create the contours of a truly transformed food system.

About the author

Karin Kleinbooi has been working with Solidaridad since 2015 and is a Senior Programme Manager at Solidaridad Southern Africa. Karin is responsible for facilitating policy advocacy through multi-stakeholder platforms with various actors (including farmers, CSOs, the private sector, Government and regional institutions). She currently focuses on value chain transparency, food systems transformation, agroecology and regenerative agriculture and creating enabling environments for sustainability.

Together with different partners and stakeholders, Karin is developing a local food systems transformation approach in Cape Town that is to inspire transformative food systems programming in the region, Africa and beyond.