Picture this: a family of four living off a half-an-acre land, growing vegetables that aren’t enough to sustain them. They rely on agriculture for income and food security, but at the same time they are not exposed to efficient ways of producing food. It is true for many rural households in Bangladesh that are unable to turn agriculture into a profitable enterprise. But then, there is another truth: where there is a will, there is a way. Here is a story of a woman farmer in Bangladesh who believed in this truth and pursued it diligently.

Meet Basonti Rani, a 40-year-old farmer from Jessore, a coastal district in Bangladesh that has been in the news for rising temperature, erratic rainfall and an increased frequency and severity of droughts. Like other parts of the country, the farmers in Jessore, especially smallholders, are up against a huge challenge: natural disasters. Hence, adopting good agricultural practices (GAP) and making efficient use of land is now all the more pervasive.

It feels like a dream I lived through. I was not the same as you see me today. It took a lot of effort at my end and from Solidaridad to bring me and my family here.

Basonti Rani

This resident of Palashi village of Monirampur sub-district in Jessore began her journey as a smallholder in the late 90s, when she and her husband started farming on a half-an-acre land. However, the journey was fraught with challenges. The couple’s allegiance to traditional agriculture didn’t pay off and their struggle to make both ends meet continued until Basonti became a part of a producer’s group organized by Solidaridad’s flagship project—Sustainable Agriculture, Food Security and Linkages (SaFaL)—in 2014.

Life took a turn for better for young Basonti, who was inducted into the training sessions on safe farming and post-harvest management. As the opportunity appeared before her, she lapped it up in no time. Under the careful guidance of trainers, Basonti learned the smart farming techniques such as use of quality seeds, vermin compost, bio-fertilisers, pheromone trap for natural pesticide control and judicious use of chemicals and fertilisers. She not only adopted the learnings from the SaFaL project in her 0.5 acre of land, but also internalised the concepts of smart agricultural practices.

I feel I am connected to the global network of farmers as I practice globally adopted agricultural technologies that other farmers across the world practice with support from Solidaridad. I have been able to reduce the cost of inputs and continue chemical-free production, which is better for consumption.

Basonti Rani

After experiencing an increase in quality and volume of production, Basonti and her family adopted the post-harvest mechanisms such as use of plastic crate, sorting, grading and other precautions suggested by the Solidaridad team. They reduced post-harvest losses. This dual support of improving production quality and quantity and preventing post-harvest losses provided by Solidaridad’s SAFAL project gave her hope that agriculture, if done the right way, has the potential to improve lives.

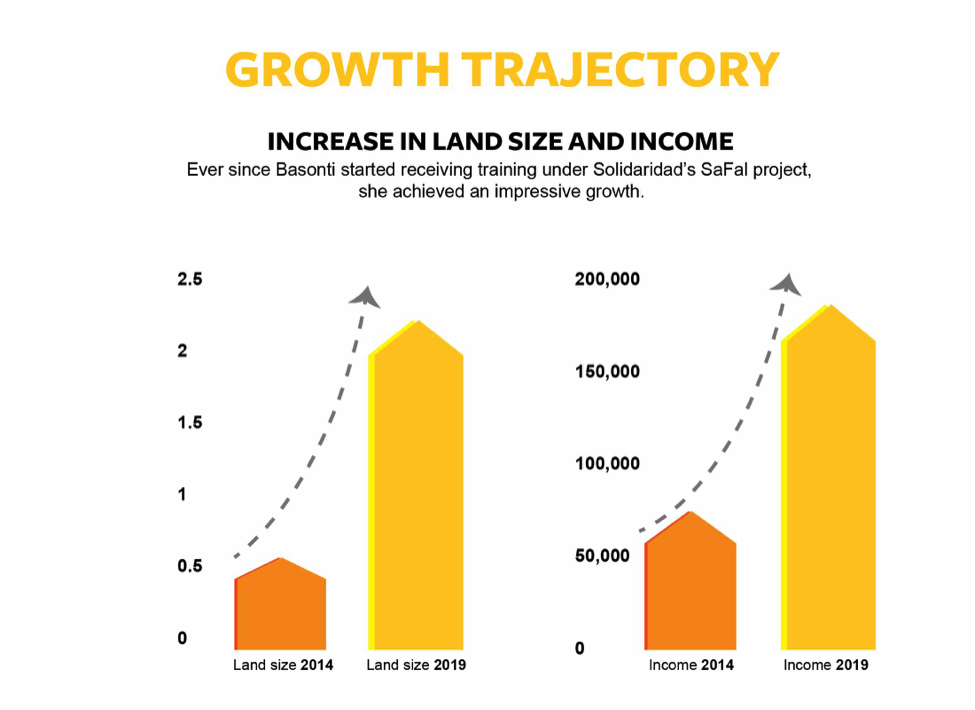

Marked change in socio-economic profile

Over the years, with improved knowledge on ecological food production and renewed enthusiasm to grow their enterprise, the land size of Basonti’s family increased by almost five times to 2.31 acres, where they grow vegetables—brinjal, cabbage, papaya, carrot, leafy vegetables—round the year. However, the most evident outcome of successfully adopting Solidaridad’s ecosystem-based farming approach has been the increase in household income. With the increase in land area and capacity of producing and marketing multiple crops round the year, her income from vegetable production increased from an average of BDT 65,000 (€ 650) to BDT 120,000 (€ 1200) in 2016, which has further gone up to BDT 180,000 (€ 1800). Basonti aspires to be a model woman farmer in her locality and wish to provide knowledge support to the struggling farmers who remain at the subsistence level.

All these efforts paid off as I am able to send my daughter to a medical school and give my son quality education. I now wish to support farmers in my village to transforming their agriculture into a safe and profitable enterprise.

Basonti Rani