“One day an engineer came and asked us for help”

Jordi Amador Escoto was 13 years old when Engineer Erick Leiva arrived at his grandfather Mercedes’ plot to request authorization to place a weather station that would feed a climate data analysis system for the area, with the aim of supporting the community’s farmers in decision making.

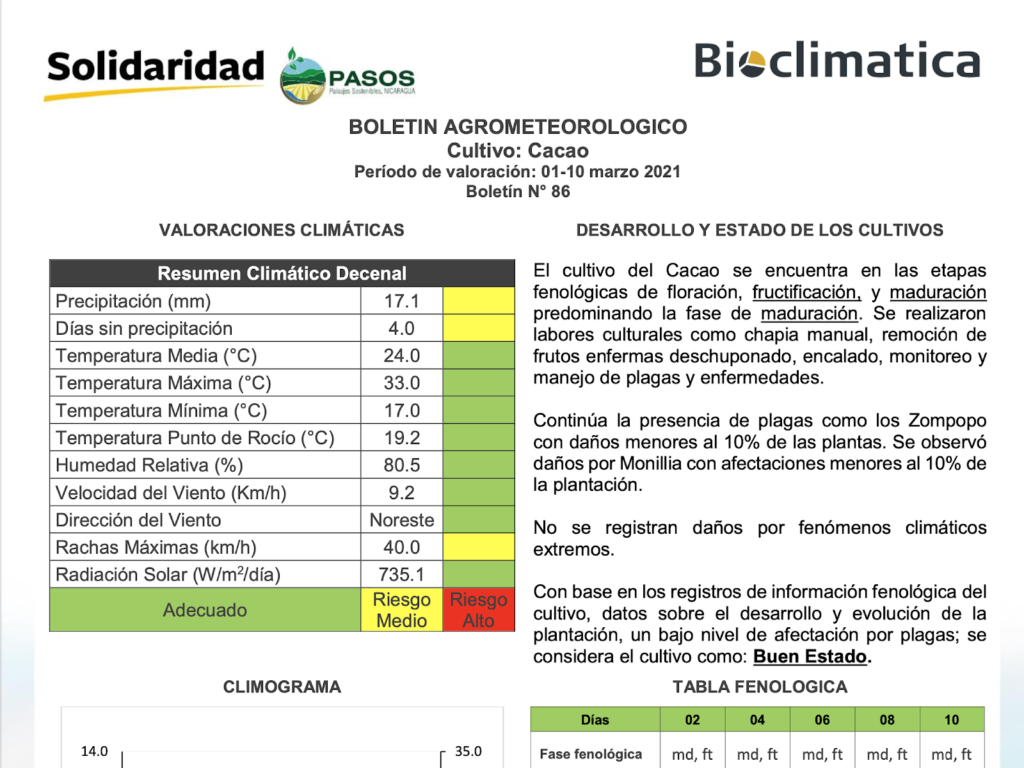

In 2018, Solidaridad created a pilot project to link smallholders in the María Cristina community, so that a service provider could give them access to quality real-time climate information. The climatic information would also be combined with phenological data captured by farmers identified by Solidaridad, thereby facilitating analysis of how the different climatic conditions influence the physiological behavior of the crops.

“The information is used for better decision-making regarding the crop-management activities that [farmers] have to perform, and it also provides recommendations of when to carry these activities out, according to the data. Farmers may also be better prepared to face the effects of climate change and its variability,” explained María Durán, Solidaridad Programme Manager in Nicaragua.

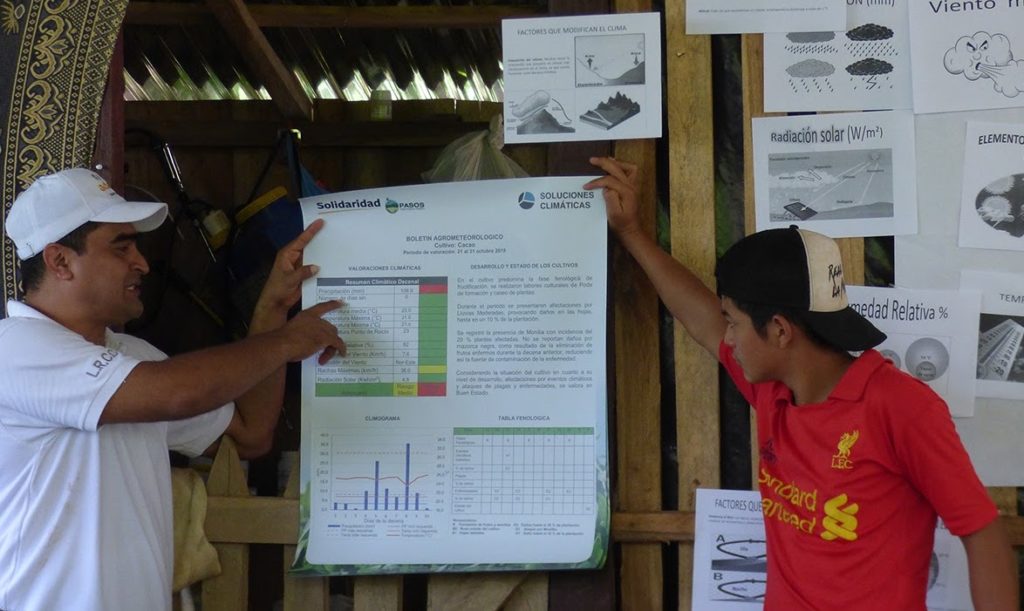

After listening to a brief explanation, in which Solidaridad requested a volunteer to take control of the station, Jordi decided to step forward. This was two years ago, and since then, every day before going to school, Jordi checks the weather station to verify that it is sending data with which the agrometeorological bulletin is prepared, which all producers in the area consult.

“I have learned to measure the rain; now I know that if atmospheric pressure drops below 1200, it is because it is going to rain. I also know that if the ultraviolet rays exceed 8 it has become a risk to leave the house, because it is harmful to the skin. I can now measure the direction and speed of the winds, the humidity, and I know the influence of the phases of the moon on the climate and the crop,” says Jordi.

“I’ve been working in the fields for many years; the weather has never been so crazy”

Mercedes Escoto León, Jordi’s grandfather, came to the María Cristina community 35 years ago. “When we started working here, we didn’t know what we were doing; in a short time the farm was destroyed and we had to start from scratch. We were learning not to burn, to conserve water and soils and the importance of restoring with diversification.”

Times have changed for Mercedes, but there have always been challenges. At first the challenge was to produce and survive, then the challenge was to maintain a certain balance between production and natural systems, but now unpredictable and extreme weather events are one of the main threats that his farm faces every day.

“On the farm I have cocoa in an agroforestry system, timber trees, medicinal plants, fruit trees and vegetables for home consumption, and a little livestock. I really like the criolla [local] varieties. Anything in the world can happen, but here there is never a lack of food; the farm provides our livelihood,” says Mercedes.

“I hear on television that it’s going to rain out of season, but what do I do?”

In the region, weather news is broadcast only on channel 10, but it is of a general nature for the country. They do not provide specific data for the area or give recommendations for crops.

The agrometeorological bulletins reach producers’ cell phones; it comes in a PDF for those who have access to WhatsApp and via text message for those who have simpler phones. In addition to including climate data and weekly forecasts, the bulletin includes a specific section on the development of and status of the predominant crops in the area, as well as management recommendations adapted to the weekly forecast.

The information allows producers to understand and prepare for climate factors that predispose to an increase in the incidence of pests or diseases.

“I am getting older. My children left for the city and did not want the farm, but Jordi is here”

When asked what he thinks is the success of his plot, Mercedes said: “There are key issues, farmer field schools, the cooperative system, demonstration plots, experiences have to be shared. There is always something new. See this about the [weather] stations; I wasn’t able to support it, but my grandson could.”

Jordi added, “I like to explain what I do and what I have learned. Ever since I was a young boy, I have lived with my grandfather and I know the countryside. Now I want to learn how to graft cocoa, and after school I would like to study agroforestry engineering, to continue working on the farm.”

The story of Jordi and his grandfather shows that nobody is too young or too old to understand the fragility of human beings and their livelihoods in the face of changing weather. They are also witnesses to how much we can improve our quality of life if we try to better understand climate and its variability.